“More than 400,000 migrant children have crossed the U.S. border without their parents since 2003” reports CNN.

This is hard to believe, but I’d like to share some of my experiences in these lands between the Rio Grande and South America.

Not counting flights south of the border, I have entered Mexico through the border at seven locations from the U.S. – from Brownsville (Matamoros) in the east to San Diego (Tijuana) in the west. I have driven with friends from the U.S. border through Mexico to Guatemala City (well over 2,000 miles). I completed my undergraduate education in Mexico and started a college program in Mexico for a consortium at the University of Pittsburgh.

Having become acquainted with post-disaster studies at Ohio State while working there on my Ph.D. in sociology, I became acquainted with natural disasters.

For various reasons I visited the aftermath of the following disasters: a 1980 earthquake in Mexico City killing some 10,000; in 1972 an earthquake devastated Managua, Nicaragua killing nearly as many as in Mexico City; in 1976 an earthquake devastating Guatemala killed 23,000; finally, Hurricane Fifi that killed over 8,000 in 1974 in Honduras.

Why this list of death and destruction? Disasters have human consequences, and deaths are only part of that.

I visited the aftermath of all these events, but became most involved after Hurricane Fifi. With my friend from Wittenberg University, we encountered officials from the U.S. Church World Service (CWS) very soon after that disaster and learned that they would be contributing 350 houses in the devastated area near San Pedro Sula, not far from the north coast.

Fortunately, we were given a grant to monitor the construction of these houses and determine the recipients’ satisfaction with their new domiciles. The responses were overwhelmingly positive. The local agencies responsible for selecting the recipients, from all indications, chose deserving and needy families.

Much was learned as the local agencies sited, selected the materials, determined the dimensions and various characteristics of the houses. Our grant, though only a few thousand dollars, enabled us to follow the houses/families for several years. The sponsoring agency was so interested in the project they flew me to New York City to report on the project at the CWS headquarters.

The housing recipients had lost their homes since they were squatters (did not own the land on which they lived) living in vulnerable locations – on steep hillsides and along waterways, essentially unclaimed or unused land. Subsequently, the champas in which they had lived were swept away or tumbled down steep hillsides. Champas are generally made of indigenous materials including straw roofs.

By interviewing the housing recipients on several occasions, we were able to see the progress the families made and their commitment to their new homes. Many turned their homes into businesses of several kinds.

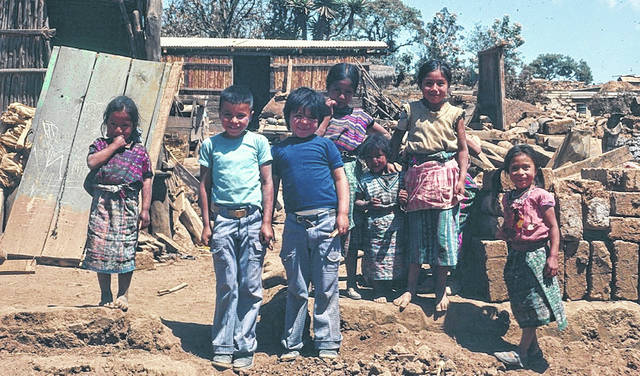

Why all this discussion of natural disasters and human misery? Simply to underline the challenges that families in the region face and describe one of the reasons that families would chance sending their children alone two or maybe three thousand miles to the U.S. border for safety and a future.

Especially in Honduras, my friend and I came to know families and on occasion watch them for years raise their children and support their families. They want for their children exactly what we want for ours, and because of a sympathetic, North American non-government organization, these families had that opportunity.

Disasters are a prime reason why these countries south of our border are so vulnerable. But there is also rampant corruption and the deadly gangs. Our country is clearly responsible for situations there – just read a history of the United Fruit Company (UFC). The term “Banana Republic” is directly related to the U.S. corporate exploitation of these lands, and the UFC is the prime example of such activity.

I can assure you that these people do not want to send their children here, nor do they want to leave their homes. The clearest solution is to assist the countries in dealing with the poverty, destruction, corruption and violence there and give them reasons to stay.

The other option is to do what we are doing – facing the chaos and cost of dealing with the present situation at the border.

Neil Snarr is Professor Emeritus of Wilmington College.