They were the heroes of a generation of baseball fans, a pair of first ballot Hall of Famers who were worth the price of admission every time they stepped on the field.

Tom Seaver liked to tell the story about how he first met Lou Brock, who mistook the baby-faced pitcher for a clubhouse attendant at the 1967 All-Star game and asked him to fetch him a soda. It wasn’t long before familiarity wasn’t a problem as Seaver and Brock dueled against each other over the next 12 years.

No one batted against Tom Terrific more than Brock. No one tried to get Brock out more than Seaver, nicknamed “The Franchise.”

It was fitting, perhaps, that both died within a few days of each other in what was a sad week for everyone who loves America’s pastime. Both battled the kind of health problems in recent years that no one who saw them in their prime would have imagined.

For those of us who reveled in their exploits it was yet another sober reminder that nothing lasts forever — even your childhood heroes. At the same time, it was also a reminder of how much of the game they once played is no longer, either.

No one is going to win 300 games again, like Seaver did with 311 over 20 years. No one is going to pitch nearly 5,000 Major League innings or complete 231 games.

No less authority than the great Los Angeles announcer Vin Scully called Seaver the best right-handed pitcher he ever saw. He would have been the greatest pitcher Scully ever saw, but there was a lefty on the Dodgers by the name of Sandy Koufax who had that honor.

That he won only one World Series in his long career wasn’t Seaver’s fault. He was on some bad teams over the years, including one in New York that didn’t become the Amazin’ Mets until Seaver picked them up and carried them to the pennant in 1969.

Seaver pitched eight straight complete games that year to end the season, winning them all and giving up a total of only eight earned runs as the Mets surged from behind to pass the Chicago Cubs in the regular season.

And while Ricky Henderson holds most stolen base records these days, no one is going to post the kind of numbers Brock did, either. He turned the stolen base into both a science and an art form with 938 in his career, including 118 in 1974 alone when he was determined to break the modern day mark of 104 set by Maury Wills in 1962.

“Lou, Lou, Lou,’’ the crowd in St. Louis used to chant when he was on first base, about to unleash his game-changing havoc.

The trade the Cubs made when they swapped Brock for Ernie Broglio in 1964 has in hindsight been called one of the worst in baseball history. But the truth is, someone like Brock would barely get a second look in today’s game, where home runs are everything and the kind of things he did on a baseball field don’t always pencil out in the analytics department.

Indeed, the biggest number that stands out in Brock’s stats — other than the stolen bases — is the 3,023 hits he piled up. Brock never hit more than 21 home runs in a career that spanned nearly two full decades, but he was so consistent that even in his last year he hit .304 and swiped 21 bases for the Cardinals.

And he was at his best when it mattered the most. Brock played in three World Series in the 1960’s, creating havoc at the plate and on the bases for the Cardinals, who won two of them. In 21 World Series games, he had 34 hits, four home runs and scored 16 runs. And, yes, he stole 14 bases.

Baseball is a different game now, driven by analytics that don’t value stolen bases or complete game wins. Trevor Bauer of the Reds leads the majors in complete games with two — both seven inning affairs — and Colorado’s Trevor Story has the stolen base lead with a grand total of 12.

Still, there’s little doubt both Seaver and Brock would have found a way to fit into today’s game. They were that good, and they were that driven.

Their passing brings back the memories of their greatness. It introduces them to another generation of baseball fans who only knew the names because their fathers and grandfathers always talked about them.

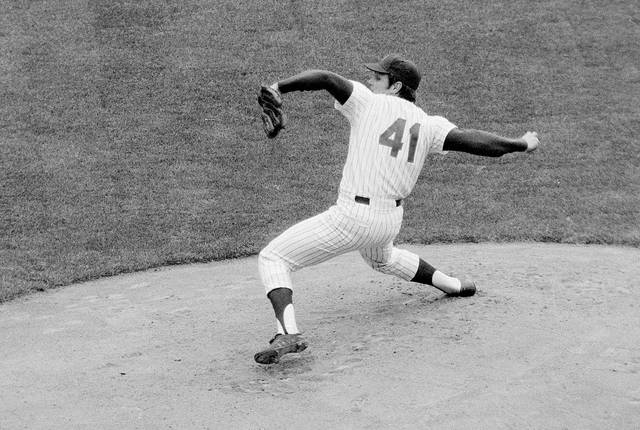

Hopefully they can picture Seaver on the mound at Shea, working from the stretch. Or Brock, inching off first, eyes fixed on the pitcher’s every movement.

Baseball as it once was played by two of the greatest who ever were.

___

Tim Dahlberg is a national sports columnist for The Associated Press. Write to him at tdahlbergap.org or http://twitter.com/timdahlberg