WILMINGTON — At the 31st annual Westheimer Peace Symposium, the Quaker sociologist and activist George Lakey predicted political polarization in the United States will get worse, but added polarization doesn’t have to block progress.

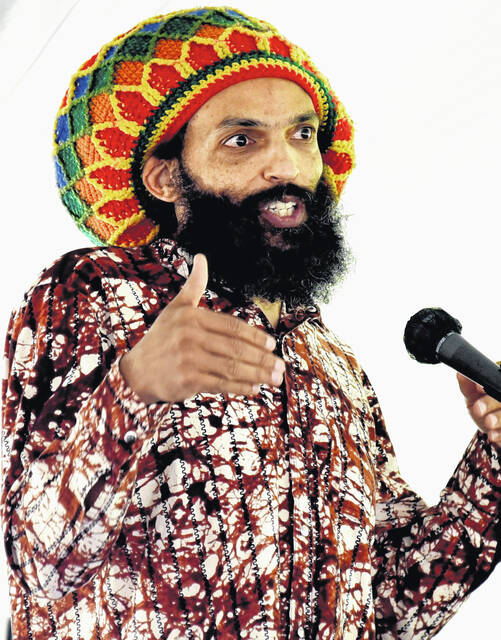

Lakey was one of two presenters at the Wilmington College peace symposium Tuesday that had the theme “A Toolbox for Nonviolent Social Change”. The other presenter was Amaha Sellassie, a Dayton-area sociologist and co-founder of the Gem City Market, a community-owned and employee-owned food co-op dedicated to increasing access to fresh fruits and vegetables in west Dayton where there was a “food desert” if you don’t count dollar stores.

The reason Lakey thinks polarization will continue to spread is because political scientists have found that political polarization is related to economic inequality, he said, and “economic inequality is definitely the curve that we’re riding and no end in sight for that.”

He’s been tracking polarization for a dozen years and was surprised to realize that progressive change can happen despite polarization. He had thought, “if everybody’s screaming at each other and nobody’s listening to each other, then how can we make progressive change?”

But history tells us polarization and progress — which Lakey defines by egalitarian principles — can coincide. He mentioned the 1930s and 1960s in the United States as examples when a time period had both polarization and progress.

So the good news, he said, is polarization doesn’t necessarily block progress, and in fact polarization appears to be favorable to progress or at least sets up conditions under which progress can more easily take place.

However, there are no guarantees, he emphasized, and polarization has also coincided with fascism assuming power in Germany and Italy.

That’s due to polarization being a social force that has no goal of its own, he said. So it’s up to us and the movements we create to set the direction, said Lakey, who is 83.

Later in the day at another symposium talk, Lakey said what polarization does is take a difference that exists among people and make a big deal out of it.

At an evening session with both presenters, Sellassie spoke about how the community in Dayton practiced their own self-determination, coming together to start a food co-op. One thing that stood out in his remarks was when he said a $50,000 donation from the Rotary civic organization “started to legitimize us.”

He also talked about the opioid scourge, noting Dayton has been hit hard. Sellassie suggested that contributing dynamics include personal trauma plus “different things in the community that make easy entry points into self-medication and opioids.”

Part of the solution, he said, is to see those who have a substance disorder and really hear their stories, to know what’s going on, “and not dehumanizing them.”

As an illustration of dehumanizing people with a drug problem, Sellassie recalls hearing people say revive an overdose patient with Narcan once.

“That was the answer … you bring them back once, the second time they’re on their own,” he remarked.

A Sinclair Community College professor, Sellassie is a member of the Dayton Human Relations Council, and co-chair of the MLK March. He is also co-founder of West Dayton Strong — an after-school and summer program in Desoto Bass public housing that’s focused on math and reading development.

Lakey has received the Martin Luther King Jr. Peace Award, the Paul Robeson Social Justice Award, the Ashley Montague International Conflict Resolution Award, and the Giraffe Award for “Sticking his Neck out for the Common Good.”

The most recent of Lakey’s 10 books is “How We Win: A Guide to Nonviolent Direct Action Campaigning”, published in 2018.

Reach Gary Huffenberger at 937-556-5768.