After the conclusion of the Civil War in 1865, a period of semi-euphoria among African Americans swept through the U.S. By reading through Wilmington’s newspapers between the end of the war and 1900, it was clear that for some time the local African American people of Wilmington felt a sense of acceptance and safety that they had apparently not previously experienced.

They felt free to sponsor and participate in parades, have public meetings (especially in the county fairgrounds) and become politically active in the Republican Party.

In my previous article for Black History Month I tried to explain this through the exceptional life of Joseph Hawley, who exemplified this trend as a successful local businessman and political participant. However, toward the end of the century, this trend changed and visions of the pre-Civil War returned.

In many ways this discussion comes down to the question of how these members of our community came to be treated as time proceeded. I found a few newspaper accounts late in the 19th century that leads one to believe that things became less friendly for our underprivileged minority citizens. Some examples will follow.

In 1878 an article in the local paper declared, “LOTS OF TROUBLE. Brides, Grooms, and a Preacher to be arrested.” The article goes on, “It is alleged that two white girls living at that point (near Sligo) married two colored fellows, last Saturday evening, Rev. Jacob Emmons performing both ceremonies. Warrants have been, or will be issued for the arrest of both brides and their husbands and Rev. Mr. Emmons. The penalty in each case, is a fine not to exceed $500 and imprisonment not to exceed six months, or both, at the option of the Magistrate.”

Rev. Emmons was the pastor of the Second Baptist Church on Grant Street (now the Bible Missionary Baptist Church). All five were arrested and spent the night in jail, but were released the next day.

The follow-up article two weeks later explained, “DISCHARGED. That Colored Case Disposed of by Mayor Hayes.” It was determined by the mayor that the statute under which this prosecution was brought was unconstitutional and void.

The racial integration of schools was an issue in the 1850s and again toward the last part of that century. The Wilmington Journal noted in August of 1885 that the new building for African American children was inspected and accepted by the school board.

A very different story appeared in the same newspaper in 1895.

The newspaper story begins with the observation that, ”… a suit was filed in the Common Pleas Court by Hayes & Swaim, in the name of James Rockhold against the Wilmington Board of Education.” Rockhold was an African American man who recently moved to Wilmington and the allegations were that the local “Board sustains separate colored schools contrary to law and compels the colored children to attend them.” The article says that all of the accusations could have been contradicted if the case came to trial, and proceeds to state that “… it is a fact so well known that Wilmington schools are very much mixed, colored pupils being in every room in every building, and since the passage of the mixed school law admission to the ‘white buildings’ never being denied and any colored child who desired to go there, the Board ever having been careful to comply strictly with the statutes.”

Soon after these events, the attorneys who filed the suit succeeded in having the suit dismissed, which ended the matter. Mr. Rockhill’s response to this was that “he did not understand the import and the force of the paper which he signed; that he did it only after solicitation, and that he has no complaint to make of the Board of Education.” From this it was concluded that he was being used by someone else and, since he was assured it would cost him nothing, “the Court relieved him of the costs and ordered that they be paid by J.R. Hawley and Ank. Wheeler, who seem to have been the principal complainants.”

Our local newspaper is not the only source of comment on this disturbing local situation. The Cleveland Gazette on July 27, 1895 observes that, “Down in Wilmington, O., the prejudiced white people are like they are in few other southern Ohio cities and towns – they don’t seem to know that the days of the separate school for Afro-American children were long since numbered… There is no law in Ohio upon which can be based the maintenance of separate schools for any class (Nationality) of people, and wherever it is done, it is a flagrant transgression of citizen rights for which there is a remedy in the courts.” (The Gazette was the oldest newspaper serving the interests of African Americans in Ohio and had the largest circulation of such newspapers.)

Thus, a very ambitious and successful African American man after the Civil War in Wilmington reached the height of success and was rapidly deposed with one misstep which apparently constituted a line not to be crossed. It seems clear that the local newspaper intentionally misstated the situation with reference to racially segregated schools in Wilmington.

Was this the beginning of over two generations of second-class citizenship for the people now referred to as African American?

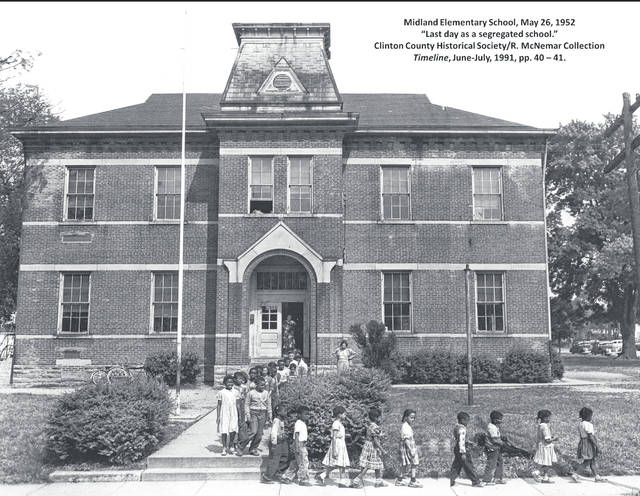

If some stories I have been told in the past few years are correct, then the answer is clearly, “Yes”, as in the first half of the 20th century, African Americans were unwelcome in local restaurants, had “special seating” in the local theater, and walked nearly two miles in both directions and past the white school to attend the segregated school at the corner of Grant and Sugartree.

The school issue came to a close in 1952 when the grade school for our black children was closed – see the photo by Bob McNemar that accompanies this story.

Neil Snarr is Professor Emeritus at Wilmington College.